Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Composed of distinct operational entities, the militant Islamist group coalition Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen serves the role of obscuring the operations of its component parts in the Sahel, thereby inhibiting a more robust response.

Djenné, Mali. (Photo: Gilles Mairet)

Highlights

- While frequently seen as a singular operational entity, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) is, in fact, a coalition of distinct militant Islamist groups with different organizational structures, leaders, and objectives.

- An estimated 75 percent of violent events attributed to JNIM are likely undertaken by the Macina Liberation Front (FLM) in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso.

- The groups comprising JNIM do not enjoy wide popular support. Rather, these groups have increasingly tapped into local criminal networks and, in the case of FLM, mounted attacks on civilian populations.

Violent events linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel—Burkina Faso, Mali, and western Niger—have surged nearly sevenfold since 2017. With more than 1,000 violent episodes reported in the past year, the Sahel experienced the largest increase in violent extremist activity of any region in Africa during this period.1 With nearly 8,000 fatalities, millions of people displaced, government officials and traditional leaders targeted, thousands of schools closed, and economic activity severely curtailed, the Sahel is staggering from the surge of attacks.

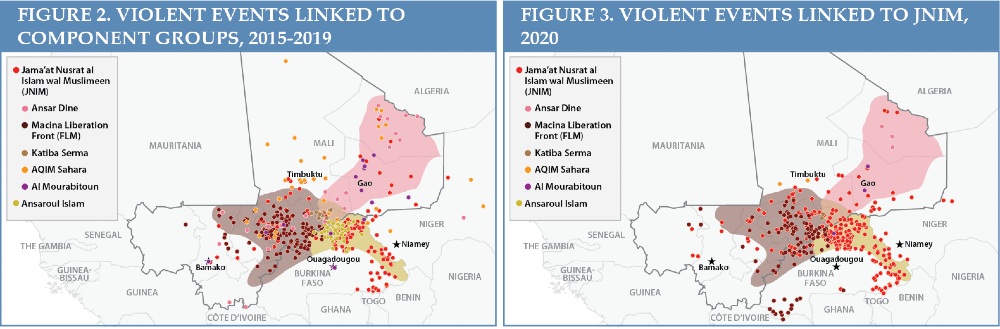

Stretching from northern Mali to southeastern Burkina Faso, violent events attributed to Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) comprise more than 64 percent of all episodes linked to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel since 2017. The Macina Liberation Front (FLM) has been by far the most active of JNIM’s component groups, operating from its stronghold in central Mali and expanding into northern and other parts of Burkina Faso.

JNIM’s structure functions as a business association on behalf of its membership, giving the impression that it is omnipresent and inexorably expanding its reach. The characterization of JNIM as a single operational entity, however, feeds the inaccurate perception of a unified command and control structure. It also obscures the local realities that have fueled militant Islamist activity in the Sahel. Treating JNIM as a unitary organization plays into the hands of the insurgents by muddying their motivations and activities, and concealing their vulnerabilities. JNIM does not necessarily have a single headquarters, operational hierarchy, or group of fighters that can be directly targeted by government security forces. Yet, with nearly two-thirds of the violence in the Sahel attributed to it, targeting JNIM is the equivalent of shadow boxing.

Who Is JNIM?

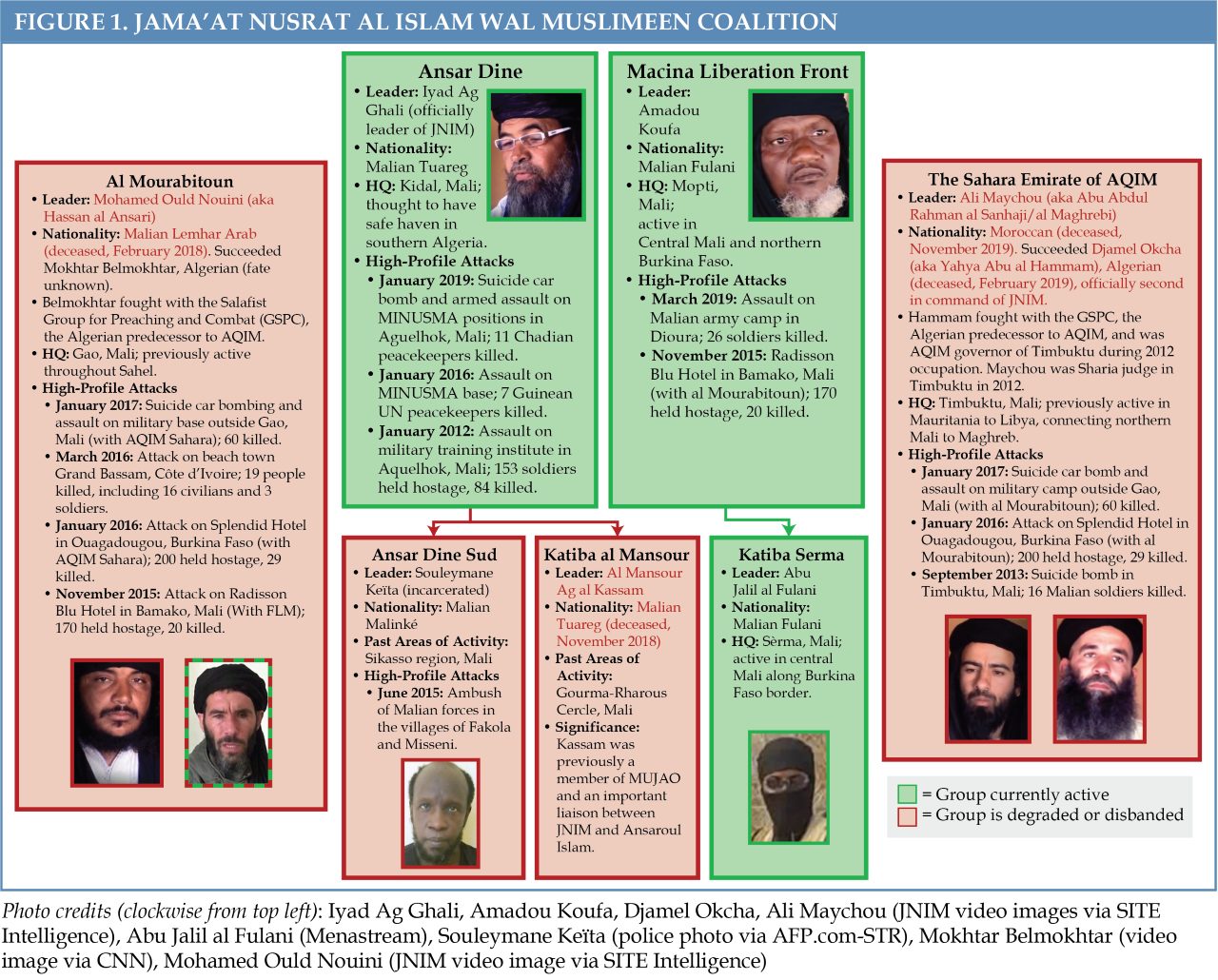

The JNIM coalition originally comprised four al Qaeda-linked militant Islamist groups in the Sahel—Ansar Dine, FLM, al Mourabitoun, and the Sahara Emirate of al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM Sahara). The composition of the groups is noteworthy in that the respective leaders represented Tuareg, Fulani, and Arab jihadists from the Sahel and Maghreb. This breadth of ethnic and geographic representation has created the illusion of a united group with expanding influence. In reality, each of these component groups have their own shifting interests, territorial influence, and motivations.2 Presently, JNIM is effectively represented by leaders of just two of the original groups—Ansar Dine’s Iyad Ag Ghali and FLM’s Amadou Koufa—and a less active FLM-offshoot, Katiba Serma, led by Abu Jalil al Fulani.

Iyad Ag Ghali, the founder of Ansar Dine, is considered the leader, or emir, of JNIM. He established Ansar Dine in 2011 when the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), a Tuareg separatist movement based in northern Mali, refused to appoint him as its head. Ag Ghali, an Ifoghas Kel Adagh Tuareg, hails from the Kidal Region of northern Mali from where he participated in Tuareg rebellions beginning in the 1990s. As the leader of Ansar Dine, he formed an alliance with AQIM and the MNLA in 2012, proclaiming northern Mali an Islamic state in May of that year. By July 2012, Ansar Dine and AQIM Sahara had sidelined the Tuareg separatists, taking control of Kidal and Timbuktu, respectively.

During most of 2012, the militant Islamist groups occupied northern Mali before pushing southward toward the more populated central regions. At the request of the Malian government, a French and African military intervention (Operational Serval), launched in January 2013, succeeded in dispersing the militants to the countryside where they took refuge in northern Mali’s rugged and vast terrain. Ag Ghali has since used Ansar Dine’s fighters to establish an enclave of political influence in northern Mali and among its various armed groups.

Amadou Koufa originally fought within the ranks of Ansar Dine in 2012 and 2013. After Ansar Dine’s dispersal following Operation Serval, Koufa began preaching extremism throughout central Mali. Born in Niafunké, Mali, and a member of the Fulani community, Koufa is believed to have been radicalized via contacts with Pakistani preachers from the Dawa sect in the 2000s.3 To rally support, Koufa tapped into local grievances harbored by Fulani pastoralists as he simultaneously called for the establishment of an Islamic theocracy. By 2015, with the help of local kinsmen, Koufa had successfully established a following in central Mali.

As the leader of FLM, Amadou Koufa has waged the deadliest insurgency of any JNIM group, attempting to topple existing traditional authorities and to promulgate his view of Sharia over central Mali. FLM’s activities and influence extended to northern Burkina Faso through connections with Ansaroul Islam, a Burkinabè militant Islamist group started by one of Koufa’s protegés, Ibrahim Dicko.

In the wake of Dicko’s death in 2017, groups of militant Islamist fighters spread their operations along the Burkina Faso-Niger border tapping into existing criminal networks. Other remnants of Ansaroul Islam reintegrated with FLM as it pushed farther south from central Mali into northern and northcentral Burkina Faso. With increasingly violent tactics, FLM has made rapid progress in these more densely populated areas, reaping from a larger pool for recruitment and revenue generation.

Experts believe that JNIM-affiliated groups jointly earn between $18 and $35 million annually, mostly through extortion of the transit routes under their control, communities engaged in artisanal mining, and to a lesser extent kidnapping for ransom.4

Even though JNIM is linked to AQIM, AQIM never developed a significant base of local support in the Sahel. Furthermore, its regional influence, even in Algeria where it first emerged, is waning.5 The deaths of al Qaeda-linked leaders Abdekmalek Droukdel (AQIM), Djamel Okcha and Ali Maychou (AQIM Sahara), and Mohamed Ould Nouini (al Mourabitoun), have likely hastened the erosion of any direct influence the global al Qaeda network could claim over JNIM-affiliated fighters. Ambiguity over the current status of AQIM Sahara and al Mourabitoun, meanwhile, underscores a key function of JNIM. By presenting a united front, the JNIM coalition obscures the many setbacks that each of these groups has experienced, providing the illusion of cohesion, command and control, and unassailability.

This illusion has been driven by the near doubling of violent activities and associated fatalities in the Sahel each year since 2016. This, however, is almost exclusively a result of FLM. FLM’s affiliation with the JNIM coalition masks its rising profile and limits the attention that international and regional forces pay to the group.

Differing Objectives, Tactics, and Territories

Although JNIM presents itself as a united front for Salafist jihad in the Sahel, there are four distinct areas of operation, driven by local dynamics, shaping the actions of JNIM’s component groups.

Northern Mali. Since its creation, Ansar Dine has competed with other Tuareg separatist groups to become a key player in northern Mali and southern Algeria. Ag Ghali has proven to be a deft political actor in northern Mali, maintaining links to secular leaders in the Tuareg community and using these connections to maintain his own safety as well as political influence. While Ag Ghali and Ansar Dine may not be directly engaged in drug trafficking or illicit smuggling, it is well established that they extort members of transnational organized crime networks in northern Mali by taxing the routes that drug traffickers rely on to move their products.6

Ag Ghali’s history of collaboration with the leadership of AQIM Sahara and al Mourabitoun connected him to networks ranging across the Sahel and Maghreb. Less locally embedded, AQIM Sahara and al Mourabitoun provided access to well-established smuggling operations across these regions, generating significant revenue for their organizations. Following the deaths of AQIM Sahara’s and al Mourabitoun’s leaders, these operations have likely been assumed by Ansar Dine, further strengthening Ag Ghali’s influence in northern Mali.

Central Mali and Northern Burkina Faso. Amadou Koufa, FLM, and its affiliates (including Katiba Serma) have promoted violent extremism to stoke inter- and intracommunal tensions within Malian society. The Macina Liberation Front is a direct reference to the 19th century Fulani Macina kingdom that roughly covered an area from central Mali to northern Burkina Faso. While Fulani make up a disproportionate number of militant Islamist fighters in the Sahel, FLM is not an exclusively Fulani group.7 Nor do a majority of Fulani adhere to Koufa’s views. Nevertheless, the perception of FLM as a Fulani group has fueled stigmatization and ethnically based reprisals, which Koufa has exploited for recruitment.

“Over three-quarters of the violent events and associated fatalities attributed to JNIM took place in FLM-dominated areas.”

Koufa’s attack on traditional leaders has taken place under the guise of his religious authority as an imam. FLM has imposed a harsh version of Sharia to solve disputes, instituted a new tax (zakat), and imposed strict behavior rules (especially on women) over dozens of villages in central Mali. In many of these areas, FLM militants have effectively pushed out Malian authorities allowing them to coerce communities under their oppressive form of Islamic law. FLM has pursued a similar modus operandi across northern Burkina Faso.

In recent years, over three-quarters of the violent events and associated fatalities attributed to JNIM took place in FLM-dominated areas. FLM has also targeted civilians more than any other JNIM group. For every eight JNIM-linked militant events that targeted civilian populations, seven have taken place in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. As FLM’s influence in these areas expanded from 2018 to 2020, Koufa’s fighters targeted civilians in roughly one out of every three of their attacks.

The alliance of Koufa and Ag Ghali has advanced the individual ambitions of both leaders and has helped to stave off conflict between the two groups by effectively delineating their areas of influence and communities of interest. The aims and methods of the two groups differ, however. While Ag Ghali’s objectives seem primarily political, Koufa’s goals are clearly linked to the violent promulgation of his interpretation of Islam and, through it, social change. Indeed, members of FLM have publicly killed local imams and traditional leaders in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso who have disagreed with Koufa’s beliefs, something that has been far less common in Ansar Dine’s enclave. In northern Mali, civilians have been targeted in less than 2 percent of events attributed to JNIM member groups.

“Koufa’s fighters targeted civilians in roughly one out of every three of their attacks.”

Eastern Burkina Faso and Niger Borderlands. Starting in 2019, there was a surge of violent activity attributed to JNIM in eastern Burkina Faso along the border with Niger, eventually extending to areas near the borders with Benin and Togo. These attacks are outside of FLM’s or Ansar Dine’s historical areas of operation and it is unclear which component groups are responsible. Rather than being ideologically or politically motivated, these events seem aimed at controlling artisanal gold mining and commercial routes. These revenues represent a potentially lucrative source of income. Estimates are that artisanal sites in areas affected by militant Islamist violence have the capacity to produce upwards of 725 kg of gold, valued at $34 million, per year.8 Expansive conservation and nature reserves in this area, moreover, provide cover for militant Islamist groups seeking to avoid detection. Such links to criminal, smuggling, and poaching groups in this border area have advanced JNIM’s reputation as an ever-expanding security threat.

Southwestern Burkina Faso. The tri-border area between Burkina Faso, Mali, and Côte d’Ivoire is characterized by illicit smuggling and small arms trafficking that accompany goods being transported through Côte d’Ivoire to commercial hubs in Mali and Burkina Faso. This area is also developing into a new hub of artisanal gold mining. A string of FLM attacks starting in 2020, combined with prospects for gold exploitation, have heightened the risk of insecurity in this region.9 As in eastern Burkina Faso, FLM fighters may be seeking to establish a presence in southwestern Burkina Faso to capture some of the illicit funds generated from these activities.

Strengths of the JNIM Structure

JNIM’s coalition structure provides it a number of advantages. These primarily revolve around its ambiguity. The failure to disaggregate JNIM and analyze its various entities, their objectives, and their functions within the larger coalition, leads to misperceptions about their organizational strength, capacity, and local support. It also overlooks potential vulnerabilities of the specific insurgencies.

The failure to designate attacks beyond a generic JNIM entity lowers the international and regional profiles of each group. This ambiguity reduces the scrutiny given to each component group making it more challenging to track specific groups’ operations and methods. This, in turn, inhibits a targeted response to confront each JNIM member. By treating all incidents as from a single organizational structure, security forces have found themselves using a blunt response that has at times worsened relations between communities and the security sector, all to the benefit of the JNIM groups.

Casting JNIM as a singular actor that operates throughout the region—and pointing to a constant stream of reported violent events as proof—promotes a perception of activity, support, and influence that far exceeds JNIM’s actual standing. The majority of events attributed to JNIM go unclaimed, making it harder to assign responsibility for attacks to specific groups and therefore respond appropriately. In fact, as Figures 2 and 3 show, the violent activities attributed to JNIM largely mirror the historical areas of influence of the component groups. This indicates a high degree of consistency and that the perceived expansiveness of JNIM is, in fact, from the composite groups.

Shaded swaths show historical areas of influence for Ansar Dine, Ansaroul Islam, FLM, and Katiba Serma

Note: Data points represent violent events involving the designated groups from 2015 through September 30, 2020. Areas of influence are illustrative and not to be interpreted as precise or constant delineations.

Data Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project

The notion of a uniform JNIM, likewise, disguises the churn of leaders and fighters in their component parts. For example, following the deaths of al Mourabitoun’s and AQIM Sahara’s leaders, no identifiable new leadership has stepped forward. Similarly, it is unclear what happened to the rank and file fighters. They may have been integrated into other militant Islamist contingents in the region—or they may have simply blended into local communities. Given the extensive ties to criminal enterprises throughout the Sahel, they could also have joined the networks of transnational organized crime in northern Mali or smuggling and artisanal gold mining outfits in Burkina Faso. Consequently, while al Mourabitoun and AQIM Sahara may now be seriously degraded or even defunct, the ambiguity of JNIM’s structure masks their setbacks and makes the campaign to counter them more difficult.

Weaknesses of the JNIM Organizational Structure

While Ag Ghali and Koufa are the sole figureheads of the coalition, it is unclear how much sway either actually holds over the different JNIM elements dispersed across the region. They are also likely unable to stop bands of insurgents from devolving into criminality or even defecting to competing groups.

FLM, for example, has experienced internal dissension over fighters’ ability to levy taxes on grazing lands and the distribution of loot taken in battle.10 Fighters often defect, realign, or strike out on their own when at odds with their leaders contributing to a fluid exchange of combatants between militant Islamist groups and other armed groups operating in the wider region.11

“FLM has been responsible for 78 percent of militant Islamist group attacks against civilians.”

The JNIM structure also likely masks strains between Ansar Dine and FLM. The brutality with which FLM has coerced communities in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso suggests a commitment to force Koufa’s extremist version of Islam onto these communities. This may ultimately pit him against a more pragmatic Ag Ghali, who appears satisfied with increasing his influence over northern Mali, as demonstrated by his 2020 exchange of four foreign hostages for the release of some 200 prisoners. As Koufa seeks to expand the theatre of FLM’s operations, he may desire to break away from JNIM’s less ideologically motivated contingents. So far, the coalitional structure has helped to ease tensions, but it seems likely the rivalries between the leaders and their lieutenants will grow.

Tensions and infighting between militant Islamist groups are not new across the Sahel and have historically defined much of their activities. Disputes over territory and resources may have reignited tensions between the JNIM groups and the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS), which also operates in the region, despite their shared origins and recent history of fighting alongside one another.12 Reports of potential negotiations between Ag Ghali and the Malian government may have further deteriorated relations with ISGS. Additional negotiations with the government may also isolate Ag Ghali from more ideologically motivated jihadists within JNIM’s ranks.13

To sustain themselves, insurgencies need a degree of popular support. That the growing percentage of attacks against civilians has increased as FLM has expanded its reach from central Mali, suggests a lack of such support. Since October 2018, FLM has been responsible for 78 percent of militant Islamist group attacks against civilians attributed to JNIM. This presents a stark contrast to JNIM’s other groups and areas of operations, suggesting continued popular resistance in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso.14

Recommendations

The surge of militant Islamist group violence in the Sahel has alarmed communities and governments across the region. Groups aligned with JNIM, primarily FLM and Ansar Dine, are linked to the bulk of this violence. Security actors need to resist the image of JNIM as a single entity and undertake the difficult analytic work to deconstruct JNIM into its component parts to counter their destabilizing actions.

Stop treating JNIM as a singular operational entity. Dealing with a coalition of insurgents requires a multitiered approach. It is important to identify and isolate the main operational groups against which action can be taken to degrade the JNIM coalition. This primarily means raising the profile of FLM and Ansar Dine. It also demands better identifying those elements operating in northern and eastern Burkina Faso. This will require enhanced intelligence gathering and sharing by governments in the region to generate information, analysis, and education about where and how the different component groups operate. Scrutinizing and targeting distinct entities provides a more tangible enemy, revealing their differences and weaknesses. Doing so can also demystify JNIM and expose the lack of local support the component groups receive.

Strengthen counterinsurgency operations in Central Mali and Northern Burkina Faso. Targeting FLM will require more robust counterinsurgency tactics. Sustaining a security presence in key locations to apply pressure on FLM’s fighters and to disrupt their ability to move freely between central Mali and northern Burkina Faso will strain their ability to organize and launch attacks.15 Similarly, actions to counter FLM’s efforts to expand into southwestern Burkina Faso should aim to cut off fighters in this area from FLM’s base of operations in central Mali. Because this appears to be a relatively new theatre of operations for FLM’s activities, fighters in southwestern Burkina Faso are unlikely to be self-sustaining. Thus, targeting these groups and their movements and connections to Koufa may prove particularly disruptive.

Target illicit networks allied with Ansar Dine. Ansar Dine and Ag Ghali are well entrenched in northern Malian politics and its different separatist armed groups. In addition to counterinsurgency operations, law enforcement efforts targeting the illicit networks that Ansar Dine facilitates would disrupt Ag Ghali’s operations. If smugglers and local authorities allied with Ansar Dine determine that their collaboration brings a higher degree of scrutiny and probability of arrest, then Ag Ghali may lose the political clout he has sought to cultivate. Undermining Ag Ghali’s political standing, as well as depriving him of his sources of financing and allies, may help accelerate the dismantling of Ansar Dine.

Protect contested communities. Counterinsurgency forces should recognize that the vast majority of local populations reject and fear JNIM-affiliated militant Islamist groups, especially FLM, and these communities desire help and support from security forces. Government representatives and security forces must place a premium on building strong relationships with local communities in the affected areas. This will require a discriminating response lest it damage relations between the security forces and local communities. The metric should not be how many militants have been killed but how much government presence can be sustained in these communities.

Working alongside community leaders and civil society to devise plans to protect communities will help undo the efforts of FLM and its affiliated groups to intimidate communities through violence against civilians. This will require increased and continuous security for those communities in contested areas. It also demands that local leaders receive protection, as they are more likely to be targeted by militant Islamist groups if they are perceived to be collaborating with the government.16 The voices of nonviolent communal leaders resisting intimidation from militant Islamist groups require amplification and protection.

Militants at a training camp in central Mali. (Image: Screen capture/Long War Journal)

In other contexts, communities may need to be reassured that after being forced to work with militant Islamist groups they will not face a heavy-handed response from security forces. Communities engaged in artisanal mining or along popular smuggling routes may be leery of the increased presence of security forces. Consequently, national and local governments should devise programs and policies that help to legitimize the economies of these communities. Collaborating closely with local leaders to better regulate artisanal mining and transportation will help to restore security and safety to ordinary citizens. Security, in turn will expand economic opportunities for these communities. This approach will also disrupt the ability of militant Islamist groups to capture revenues from illicit activities without seriously disrupting local economies.

Continue to pursue political settlements. Ag Ghali and Koufa have reportedly engaged in negotiations with the Malian government and at times local authorities, showing at least the willingness to consider a cessation in fighting. Often their demands are inconceivable, such as the full withdrawal of French troops from the region or the public enactment of an extreme interpretation of Sharia. Nevertheless, continuing this dialogue is valuable for exploring political avenues for resolving the conflict.

Negotiations also require the respective leaders to take positions on key issues. This is important for understanding the objectives of the leaders as well as educating the public on what is at stake in the conflict. Dialogue may also reveal key differences between the various militant Islamist group factions. Disparities between Ag Ghali and Koufa’s goals, such as how to interpret and implement Sharia, may further weaken the cohesion of their coalition. The willingness of Ag Ghali and Koufa to engage in settlements with national authorities may also split fighters seeking a political agreement from hardline factions within their ranks.

Devise policies of reintegration for lower level fighters. National and local governments can capitalize on internal tensions and the constant churn of commanders by providing clear pathways out of militant Islamist groups for combatants. Lower level fighters have varying levels of commitment. By engaging in dialogue with mid- and lower level commanders, national and local governments may tease out these fighters’ motivations and reveal opportunities for disarmament, which would further erode a key asset perpetuating FLM and Ansar Dine.

Reintegration policies should target these lower level fighters. This will require enhanced practices to encourage defections while conveying messages from governments and local leaders that these fighters have other options. Experience from other reintegration contexts has highlighted the importance of working with communities to facilitate this transition lest fighters revert to their jihadist networks. As these fighters are likely to know one another, the motivations of Ag Ghali or Koufa may not matter as much to the fighters as their personal connections and opportunities. Amnesty and reintegration programs played a significant role in weakening the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat insurgency in Algeria and similar policies have debilitated militant Islamist insurgencies elsewhere. If national governments can offer assurances of safety and eventually opportunities beyond being a hired gun, that may persuade lower level fighters to surrender in the Sahel as well.

Dr. Daniel Eizenga is a Research Fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Ms. Wendy Williams is an Associate Research Fellow at the Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

Notes

- ⇑ All violent event and fatality data attributed to the JNIM component groups come from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project database.

- ⇑ Alex Thurston, Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Confronting Central Mali’s Extremist Threat,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 22, 2019.

- ⇑ Christian Nellemann, R. Henriksen, Riccardo Pravettoni, D. Stewart, M. Kotsovou, M.A.J. Schlingemann, Mark Shaw, and Tuesday Reitano, eds., “World Atlas of Illicit Flows: A RHIPTO-INTERPOL-GI Assessment” (Oslo: RHIPTO Norwegian Center for Global Analyses, 2018), 8.

- ⇑ Geoff D. Porter, “AQIM Pleads for Relevance in Algeria,” CTC Sentinel 12, no. 3 (West Point: Combating Terrorism Center, 2019).

- ⇑ Peter Tinti, “Drug Trafficking in Northern Mali: A Tenuous Criminal Equilibrium,” ENACT Research Paper No. 14, September 2020.

- ⇑ Modibo Ghaly Cissé, “Understanding Fulani Perspectives on the Sahel Crisis,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 22, 2020.

- ⇑ David Lewis and Ryan McNeil, “How Jihadists Struck Gold in Africa’s Sahel,” Reuters, November 22, 2019.

- ⇑ Roberto Sollazzo and Matthias Nowak, “Tri-Border Transit: Trafficking and Smuggling in the Burkina Faso-Côte d’Ivoire-Mali Region,” Security Assessment in North Africa, Small Arms Survey, October 2020.

- ⇑ Héni Nsaibia and Caleb Weiss, “The End of the Sahelian Anomaly: How the Global Conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida Finally Came to West Africa,” CTC Sentinel 13, no. 7 (West Point: Combating Terrorism Center, 2020), 11.

- ⇑ Andrew Lebovich, “Mapping Armed Groups in Mali and in the Sahel,” European Council on Foreign Relations (2019).

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Exploiting Borders in the Sahel: The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 10, 2019.

- ⇑ Alex Thurston, “Political Settlements with Jihadists in Algeria and the Sahel,” West African Papers No. 18 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2018).

- ⇑ Anouar Boukhars, “The Logic of Violence in Africa’s Extremist Insurgencies,” Perspectives on Terrorism 14, no. 5 (2020).

- ⇑ Pauline Le Roux, “Responding to the Rise in Violent Extremism in the Sahel,” Africa Security Brief No. 36 (Washington, DC: Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 2019).

- ⇑ Fransje Molenaar, Jonathan Tossell, Anna Schmauder, Rahmane Idrissa, and Rida Lyammouri, “The Status Quo Defied: The Legitimacy of Traditional Authorities in Areas of Limited Statehood in Mali, Niger and Libya,” CRU Report (The Hague: Clingendael Netherlands Institute of International Relations, 2019).